![This article is part of the project Worlds of Women - International Material in ARAB’s Collections]()

International Women’s Day is one of the socialist inventions that have spread and become a successful feminist celebration all over the world. The significance of International Women’s Day has certainly changed since its inception when it was intended to function as an international day for agitating for women’s suffrage to when it became an official United Nations Day in the 1970s to the present day when it is used by major companies to celebrate their outstanding female employee.

Stockholm, 12 November 1980

Dear Fredrikor,

We have now conducted a number of discussions within our organization and come to the conclusion that, as representatives of the socialist women’s movement, we cannot take part in a joint cross-party 8 March demonstration. After all, from a historical perspective, 8 March is the International Socialist Women’s Day and our organization feels that this should absolutely remain the case. Changing this would be like changing 1 May. For this reason, we are unable to endorse the UN’s appeal.

This should in no way be interpreted as meaning that we are averse or unwilling to work with other women’s organizations. Indeed, we have already had fruitful cross-party collaboration, first and foremost with the FBA, and will continue to do so in the future. Moreover, we would like to extend our thanks for the invitation to take part in a joint 8 March demonstration. (1)

Grupp 8 in Stockholm

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén

The letter from the left-wing feminist Grupp 8 in Stockholm to the feminist Fredrika Bremer Association, a liberal, middle-class organization, illustrates the historical development of International Women’s Day (IWD) very well: In the very beginning, IWD was entirely a socialist project. However, the historical development of this project has turned it into a much broader international feminist project. In 1977, it became a United Nations Day for women’s rights and international peace to be observed on any day of the year by member states in accordance with their historical and national traditions. (2) Today, IWD is celebrated all over the world. It is no longer entirely associated with a socialist project. For instance, every year on IWD, the Swedish business journal Veckans Affärer announces the 125 most powerful women in Swedish business. (3)

The history of IWD has many similarities with May Day, as has been pointed out by Temma Kaplan. (4) Both celebrations were an attempt to unite the movement around common goals celebrated as a national day on a Sunday; both had their origins in the United States and were officially introduced by a decision taken by an international organization.

The historical development of IWD makes it an interesting research subject. But IWD is not only interesting as a subject itself, it can also be used as a prism for a variety of historical developments:

- IWD illustrates the international ambitions, the reality women encountered internationally, and the connection between the international and the regional level. IWD can be used to analyze both the form and the content of this international work. It also provides a good basis for a gender analysis of internationalism.

- It can be used to analyze the ways in which the different forms of globalization have structured women’s political struggle during the last 100 years.

- An analysis of the historical writing on IWD can illustrate how class and gender have functioned as categories in women’s own storytelling, showing their historical-political strategies when writing history.

Below, I am going to trace the content and the form of IWD over the last 100 years as it is represented in the collections of the Labour Movement Archives and Library (ARAB) to show that this material is a good starting point for an international study of the above-mentioned historical problems and questions.

1. International Women’s Day in the ARAB collections

The material on IWD is scattered, probably not only in the ARAB collections, but also in most archives and libraries. This not only makes it difficult to find, but also difficult to describe coherently. The fact that the material is spread over many archives of different organizations and individuals and that different journals, both Swedish and non-Swedish, have been reporting about it since its very beginning says something about the popularity of this international initiative among a variety of both organizations and geographical areas.

I have traced the material in the collections by starting with the minutes of the Copenhagen conference and following how IWD was arranged in the different countries by looking at the national women’s journals, which can easily be found using the library catalogues Kata or Libris. The dates of the different celebrations mentioned in the journals have been very useful in order to follow discussions in the minutes of national and international organizations. Moreover, the archival finding aid Calm has been very useful for discovering individual documents as well as brochures which sometimes are stored in the archives, although we would expect them to be in the library. This is especially true for non-Swedish material. Often the so-called collections, which can consist of one or two issues of one journal, are very helpful in order to get an idea if the material can be useful and to find the complete series at other archives and libraries. The collections on international socialist women and the collection on international communist women are especially interesting. These printed matters often came to Sweden via contacts between Swedish and foreign organizations and were part of archival collections. Sometimes these printed matters have been incorporated into the library and sometimes they have become a separate collection.

Although materials in a range of different languages can be found in the ARAB collections, the dominant language for the first half of the twentieth century was German. Even though relations with German women were still of relevance to the Swedish labour movement, the publications and letters in English were growing in number and since the 1970s English has been the dominant language. Printed material, stored in the library and easy to find via the library catalogue Kata, is more substantial than the archival material; however, both printed and non-printed materials make a fascinating collection.

The material can be divided into three different categories:

- Minutes

- Printed reports in journals

- Correspondence and speeches

Minutes and annual reports include both Swedish and non-Swedish material. The latter has normally been produced by international organizations and has been transferred to Swedish organizations where it has become part of a Swedish organization’s archive. Most of the archives of the sending international organizations are-if they still exist-stored at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. Non-Swedish material includes the minutes and reports of the Labour and Socialist International (LSI) Women’s Committee, which was founded in 1927. The minutes were published in the women’s supplement to International Information, the LSI Bulletin. It was published in English, German, and French. Most of the volumes are in German (Internationale Information), but a few volumes in English can be found in the collections. Only the German version is available for the period between 1928 and 1938. The women’s supplement (Frauenbeilage) included minutes of the executive meetings, conference proceedings, and reports from the different national organizations. The reports were published once a year and included information on activities, but also the political situation and development in the different countries. For the period until the Second World War, these reports not only give a good picture of when and how IWD was celebrated, they can also be used as a short introduction to the different socialist women’s sections in Europe. They offer a brief overview of the number of members, the political strength of women in parliament, the political agenda, opportunities in a special national context, and women’s links to their party.

The women’s bulletin, published by the Socialist International after 1945, does not include the same regular reports from the different member organizations; instead, it includes not only longer articles on specific themes, such as women in The Global South countries, women’s suppression under dictatorship, and working women, but also the international messages from the international branch of the organization to their member organization at the national level.

The writing of the minutes and annual reports of the Swedish social democratic women’s organization began in 1907. The minutes of the executive committee are well preserved and show how the organization worked, although they only mirror the result of discussions. The very same is true for Swedish communist women’s groups. These minutes also illustrate the attempts to coordinate the work between local and national organizations. The annual reports are printed and often include reports on national activities as a result of international contacts. The minutes are only available in Swedish; however, there are some copies of reports and articles that Swedish activists had sent abroad.

Among other organizations of interest is also the Svenska Kvinnors Vänsterförbund, Left Federation of Swedish Women (SKV), a member organization of the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF). The SKV was a non-party women’s organization working for a democratic society with an economy not based on profit but on people’s needs, a society free from oppression. It started as a liberal women’s organization, but gradually became an organization for women from the political Left. Grupp 8 started as a ‘secret’ feminist group in 1968; among the founders were women from the Swedish Communist Party, but, in 1970, it opened its doors and others were invited to join.

Another interesting archive is that of 8:e Mars kommittén. 8 March Committee, an umbrella organization based in Stockholm that organized the IWD celebrations in Stockholm at the end of the 1970s and at the beginning of the 1980s. It is not clear if this organization was even active before and after 1980-81, but it would certainly be worth investigating.

Personal archives, such as Brita Åkerman’s, Maj-Britt Theorin’s, and Liselott Croner’s, include scattered documents on IWD, such as speeches, their preparation, and some correspondence between the organizer and the speaker.

All this material originating from Swedish organizations is different from the above-mentioned material that is part of these organization’s archives stored at ARAB.

Correspondence on IWD is not only very difficult to find in the collections, but is also very scarce. First of all, the ARAB collections include only a small amount of letters written by women activists during the first half of the twentieth century. The correspondence between Clara Zetkin and Swedish women as well as the letters exchanged between different women’s organizations are exceptions worth mentioning. In order to find information, one needs to know who the author is.

While minutes can show the strategies and the ambitions behind organizations’ IWD celebrations, journals often include reports from the three levels of women’s organizing: local, national, and international, and IWD was often the subject of these reports. Journal reports can also be used to make up for the lack of formal letters sent between the international and the national level.

The ARAB collections include an impressive collection of women’s journals from a range of different countries, among them English-, French-, and German-language journals. Some of the journals were only kept for a short period of time. Many of them were part of a comprehensive exchange of journals between different editors. They themselves are an illustration of the extensive network between different women’s organizations. How many of these exchanged issues really were read is more difficult to tell. These women’s journals can easily be found in the library catalogue Kata.

2. From suffrage to world peace-issues on the agenda

In agreement with the class-conscious political and trade organisations of the proletariat in their respective countries, the socialist women of all nationalities will hold each year a Women’s Day, whose foremost purpose it must be to aid the attainment of women’s suffrage. This demand must be handled in conjunction with the entire women’s question according to socialist precepts. The Women’s Day must have an international character and is to be prepared carefully.

Clara Zetkin, Käte Duncker, and other comrades (5)

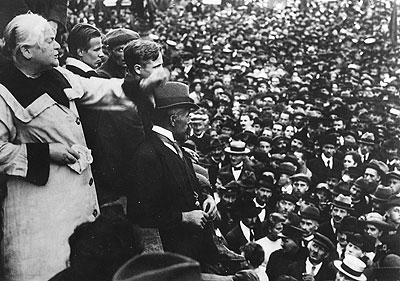

With these words, Clara Zetkin and her comrades started the long-standing tradition of IWD at the International Socialist Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in August 1910. (6) As a result of the difficulties to campaign for universal women’s suffrage in socialist organizations, Zetkin and her comrades suggested this day as a political practice in order for working-class women to campaign. Zetkin and her comrades were also concerned about the legitimacy of this political tool in the entire labour movement and stressed, therefore, that campaigns had to be conducted in agreement with the movement.

Women received political rights in many Western countries after World War I, but IWD is still today a demonstration for women’s rights. What were the demands over time and how did they change?

For adult suffrage

On 19 March 1911, more than 20,000 Austrian women demonstrated in Vienna. It was the first time IWD was officially celebrated after the decision in Copenhagen. The Austrian newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung wrote in 1911:

This new, unusual appearance; women marching behind red banners!

Serious and silent; the march is breathing the dignity of the moment. This large and daunting march although it is only in its beginning-although a beginning of an impressive size. [...] They have risen in order to, for the first time, demonstrate for their rights, the same political right as the ruling gender. (7)

Quotation from Wolfgang Maderthaner (ed.), Der internationale Frauentag in Österreich: von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, Wien 2005, 5

According to the decision taken in Copenhagen, the theme of the demonstrations in Vienna was ‘equal rights’. Besides the protection of mothers, social insurance, and the protection of working women, women’s suffrage was proposed as the most important political means to change women’s position in society. (8) Until World War II, equal rights, the protection of mothers and children, as well as women’s right to work and equal pay were the recurring demands of socialist women. It was a time when women’s issues were not at the heart of the labour movement’s policies. (9) It was also at a time when Clara Zetkin was regarded as someone who had become distracted by women’s issues and who did not have time for the real problems in the world, as Rosa Luxemburg complained to Leo Jogiches in a letter. (10) These demands for women’s rights were reinforced through the legitimacy they gained through an international socialist women’s network, but they became also more visible. The demands were not only read aloud during meetings and demonstrations, but they were also published both in advance and afterwards in the different national socialist women’s journals and in translations of reports sent between the different national organizations.

The demand for suffrage was a matter of national legislation. Women from Liberal and Conservative groups had already formed international organizations that were working for female suffrage. The International Council of Women (IWC), for instance, did not demand women’s suffrage although it was an international women’s organization whose members were national umbrella organizations. (11) The International Suffrage Alliance did, however, demand women’s suffrage based on the same conditions for men. This was sharply condemned by Zetkin and many other socialists as this could, in some cases, imply access to class-based suffrage. Women without a fixed income would in some countries be excluded from suffrage because of this. To dedicate an international campaign day to adult suffrage was, therefore, as much a statement against the ‘bourgeois’ women’s movement, as Zetkin called it, as a way for women to campaign to become members of the labour movement under an international star. (12) The resolutions written by Swedish communist women, and published after the introduction of adult suffrage in Sweden, refer much more to the latter purpose. But what about the international character of the celebrations Zetkin and her comrades were demanding in Copenhagen?

The resolution put forward by Swedish social democratic women in 1914 shows how they linked both the demand for women’s suffrage and solidarity with the women in the International:

Our opponents must not forget that we working women and wives of working men are also part of a broad section of public opinion that will support the forthcoming government suffrage bill, and may our women’s day, too, become an expression of solidarity with women in the International . (13)

Morgonbris, no. 2 1914

Some years later, Swedish communist women used a different way to achieve the international character. They published Clara Zetkin’s official IWD resolution alongside their own on the front page of their journal Röda Röster, not in opposition to what Zetkin wrote but reminding of the specific problems working-class women encountered and their demands to solve these problems. They demanded:

- compulsory requisitioning of certain essentials for working-class families in the greatest need, particularly for their children;

- the takeover of certain industries and areas of work by trade unions and cooperative companies;

- substantial housing production;

- the resumption of trade relations with Russia. (14)

Röda Röster, no. 5 1922

Even in the case of communist women, political issues concerning Sweden came first and international solidarity was not secondary but rather a vehicle to support these national issues in a symbolic way. These demands were not women specific but were characterized by an ideology that saw the end of capitalism as the only way to achieve women’s equality. The situation in Sweden during this historical period deteriorated as a result of 26 per cent of the male population being unemployed. (15) The Swedish communist women’s demands were, therefore, first of all, an expression of the difficult situation families, but also single women were facing at this time. But like the Swedish social democratic women in 1914, Anna Stina Pripp reminded her comrades of the importance of international solidarity in situations like this when she wrote:

But it is precisely in such hours of despondency that we must endeavour not to lose sight of our unknown comrades and their struggle. A large number of clubs may be able to accomplish what our little club cannot on its own.[...]

We must also think a little more about our comrades in other countries. Many of them have it harder than we do. Let us help them as best we can! Russia’s famine districts need immediate help; have we done everything we could have done for their starving children? [...].

Our little club is a tiny, tiny link. It is, however, part of the great chain of workers worldwide. Let us make it strong and good! This is our duty and this is what our women’s day demands of us. (16)

Röda Röster, no. 5 1922

The concept of internationalism was during this period closely connected with nationalism as two sides of the same coin. Leila Rupp has shown how internationalism was created in different ways by women’s organizations of different political colours at the turn of the twentieth century. In many cases, it was the number of different national symbols, like flags and national anthems, that created internationalism during international meetings. (17) In the case of socialist women, there was a similar problem of balancing the political situation they were confronted with in their daily work with demands that were recurring in most of the countries where the content was homogeneous or the demands were purely of an international character directed at an international body, such as the International Labour Organization or the League of Nations. Internationalism is here closely connected to homogeneity of demands, and these demands were published alongside the local/region-specific demands. At the same time, it was the number of local and national arrangements that was giving socialist internationalism strength. socialist women did, unlike other international women’s organizations during this period, sing ‘The Internationale’ together, but in different languages, and, with this, it gave a national touch to the international song. (18)

Against war and for peace

World War I postponed not only the introduction of adult suffrage in many countries, but it also had another significant role for the development of socialist women’s demands and IWD.

In 1915, it was impossible to hold IWD in any of the belligerent countries; therefore, celebrations in the neutral countries were especially noted. In Berlin, socialist women had planned more than seventeen meetings against the war, but all of them were stopped by the police. (19)

One of the most significant meetings was held in Berne, Switzerland, in March 1915 and organized by Clara Zetkin. The following report was published in the Swedish social democratic women’s journal Morgonbris but was a direct translation of the text from the German journal Die Gleichheit, where parts had been censored by the Government. Only a few issues of Die Gleichheit can be found at ARAB. It was originally circulated by Zetkin to the different national women’s groups, but it is not a complete series. The Swedish version left out the very parts that had been censored by the German Government, which indicates that the editors of Morgonbris were using the printed version of Die Gleichheit for their translation:

The Fifth Swiss Women’s Day, organized at forty locations, opposes with the deepest resentment - - -. the current war.

In the name of humanity and culture, the Swiss working women raised their voices for a swift end to - - - the bloodshed.

At the same time, they are pressing more urgently than ever for civil and human rights, political equality between men and women.

As members of the Socialist Women’s International, the Swiss Socialist women are requesting an international conference be quickly convened in Switzerland; this may contribute to establishing a Third International, from which the working class hopes to see mankind freed rapidly from the yoke of capitalism and its war horrors. (20)

Morgonbris, no. 5 1915

The demand for a Third International was a dangerous one as it deprived the Second International of its legitimacy from within the movement and this was called for by women whose interest was not regarded as the main interest of the labour movement. According to the article published in Morgonbris, representatives of French and Soviet socialist parties gave speeches and demanded peace on behalf of their parties. The following message was sent to Switzerland by French socialist women at the time of the same meeting and was read aloud.

While the war is dividing the international proletariat and, for the time being, has united the workers’ parties of the belligerent countries with the capitalists, we have remained faithful to the principles of international Socialism. We view it as a sacred duty to work in accordance with the decisions of the congress of the International even during the war. We are fighting against the chauvinism that has gripped the socialist parties, and we urge all our party comrades to remain faithful to the International and to unite their activities with ours, so as to bring about in our country a strong international movement that can support the movement created in other countries.

We are happy, and would emphasize in particular, that it is, first and foremost, the socialist women who once again raised the flag of international Socialism and answered the call of its brave international secretary. . . .

We stand with you in your campaign and shall use all our power, all our energy, to support it; we join with all those who have remained true to Socialism in saying: down with the war! Long live the Socialist Workers’ International! (21)

La Femme socialiste, Avril 1915 (in French); Morgonbris, no 5 1915 (in Swedish)

This was harsh criticism not only of the war, but also of the male comrades in the Socialist International who were participating in the war on different sides of the trenches. But, unlike the first report, the French women advised showing solidarity with the International. Louise Samoneau, who was the editor of La Femme Socialiste, was sentenced to two months in prison for publishing this message. (22) This illustrates very well the repressive political conditions women were working under during this period.

In the same issue of Morgonbris, a report on IWD in the United States was also published as a translation from Die Gleichheit. Even in the United States, demonstrations were held against the war and high food prices in order to mobilize women for the socialist movement. During 1917, many hunger demonstrations against high food prices during the war were held not only all over Europe, but also in the United States. It was also an expression of irritation at the conditions of mothers and children during the war and a simple demand for bread. (23)

The war also made it much more difficult for women to travel. British women were denied passports when they wanted to travel to the women’s peace conference in The Hague in April 1915. During wartime, these translations were, therefore, an important means in the struggle for peace. They show how women used the international arena to fight for political demands they could not make in their own countries. Translations were an easy means to compensate for the lack of education and knowledge of language among working-class women. By duplicating the message and publishing it in journals in several countries, the messages were accessible to many more women without the cost and time of travelling to international meetings. Swedish women sent messages of peace to women in the belligerent countries, such as Germany and England, by publishing their messages in German and British journals. British and German women, on their part, sent messages back via the Swedish journal Morgonbris and British women even sent messages of peace to German women via this Swedish journal and vice versa. (24)

The demand for peace and the protest against war have also been an important IWD message in Sweden since 1915. On IWD in Stockholm in 1915, Frida Stéenhoff, a well-known socialist woman, gave a long speech calling for peace. Her harangue against militarism was later even printed in a small booklet. Stéenhoff’s reason for talking about anti-militarism as an IWD issue was as follows:

The people behind militarism are men. The work of women is not militarism. One may ask in vain here, “Où est la femme?” (25)

Frida Stéenhoff, Krigets Herrar-Världens Herrar, Stockholm 1915, 10.

On more than thirty pages, she develops her argument against militarism as a product of men and she concludes:

Should not all the women’s associations in Europe and America-in practice, that would be the majority of the women of the civilized world-demand through their delegates that there should henceforth be mandatory mediation in all international disputes? (26)

Stéenhoff, ibid., 28.

This was a very essentialist way of thinking in terms of gender. Women and women’s organizations were regarded as a vehicle to stop the war, obviously because women could not take part in the war as soldiers. The demands that could be directed at citizens during the war were for a long time used as an argument against women’s suffrage: no citizen’s rights without obligations. This is, of course, only one part of the story; militant and right-wing women’s organizations had as well been collecting money for submarines and other rearmament projects. However, the demands for peace and adult suffrage were closely connected by the contemporary definitions of citizenship. These connections were no longer visible when during later periods women were reminded of the long-standing tradition of demanding peace on IWD, as Maj-Britt Theorin, a well-known Swedish peace activist, did in her IWD speech held in 1989:

Since the inception of International Women’s Day, peace issues have taken centre stage. This will be the case in 1989 too. (27)

ARAB Maj-Britt Theorin’s personal papers

Even if it is not true that the demand for peace was essential to IWD from the very first day, it had since World War I become an important element of the agendas for IWD. It was, first of all, the demand for disarmament that survived as a central element until the end of the Cold War and may also be the reason why the interest in IWD could be maintained for such a long time among women’s peace groups.

Against fascism

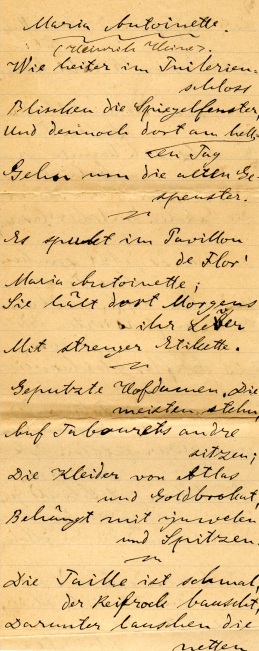

![‚Tomorrow starts International Women’s Day’. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.]()

"Tomorrow starts International Women’s Day". Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

During the inter-war period, the struggle against fascism was in many countries added to the demand for peace. Despite the fact that demonstrations were illegal in most of the fascist dictatorships during the 1930s and 1940s, several thousand women demonstrated in 1936 in Spain against fascism on IWD. (28) This was the case in many countries. In a brochure from the Democratic Women’s League of Germany (DFD), it is said that women celebrated IWD as a reminder of the resistance against fascism, not only in the different resistance groups in Poland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Norway, but also in the concentration camps, such as Ravensbrück. (29)

In 1941, in the midst of World War II, women celebrated IWD in London as a manifestation of peace and against war and fascism. (30) This manifestation was very reminiscent of the one in Berne in 1915. This time it was the British Labour Party’s chief woman officer Mary Sutherland who organized the manifestation. Sutherland had a similar position in the social democratic women’s movement as Zetkin had in the early socialist movement and was working for a global social democratic women’s movement. (31) The celebration took place in the house of the Quakers and women from different countries gave short speeches in their own languages. A report in an Austrian Festschrift published the list of speakers, which was an impressive number of leading European social democratic women, most of them living in exile. Among them were Fanny Blatny from the German-speaking Social Democrats in Czechoslovakia; Isabelle Blume from Belgium; Lydia Ciolkosz from Poland; Hertha Gotthelf, Germany; Ragna Hagen, Norway; Maria Jurneckova, Czechoslovakia; Martha Louis Lévy, France; Marianne Pollak, Austria; and Olga Treves, Italy. (32) This was probably the only occasion when international Social Democracy was meeting in public and was demonstrating unity for peace. Interestingly, Morgonbris never published a report on this meeting; the reasons are probably worth investigating as Swedish social democratic women had close relations with the women in the British Labour Party, especially with Sutherland who visited Sweden several times. (33)

However, World War I changed the content of IWD in yet another perspective. The split in the Second International and the foundation of two new Internationals, the Communist International (Comintern) and the LSI, led to different ways of celebrating IWD. Both organizations continued to promote IWD but in various ways and for different reasons.

Memorial day or time set aside for campaigns?

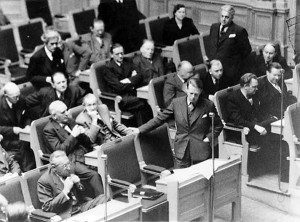

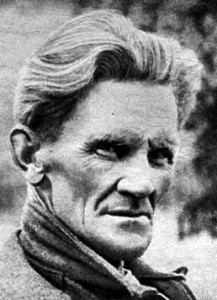

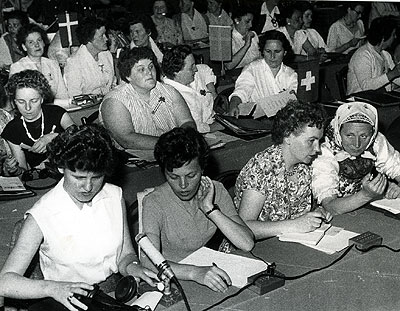

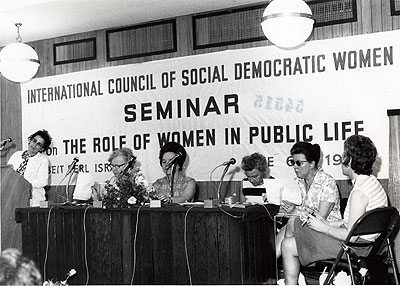

![International Council of Social Democratic women in 1973. Photo: Prager. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.]()

International Council of Social Democratic women in 1973. Photo: Prager. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

At the second women’s conference of the Comintern, held in Moscow in July 1921, Bulgarian representatives suggested an annual celebration of IWD to remember the brave women of Petrograd whose protests in 1917 against increased food prices were regarded as the trigger for the Russian Revolution. The conference accepted the proposal and for the same reason IWD became a national memorial day in the Soviet Union in 1922. (34) The Soviet Government made it a half-holiday. The working day ended at lunchtime, and men and women were given the opportunity to go to IWD meetings. (35) This turned the celebrations into a day for revolutionary memories that could be used to campaign for issues other than women’s equality.

On IWD, the demands raised by communist women showed less interest in the specific situation of women. It is an illustration of the idea that the end of capitalism will end women’s oppression. This was a way to campaign for women to become members of the communist movement. The Swedish journal Röda Röster illustrates how the revolutionary memory was transferred from former Russia to Sweden, but also how this memory was connected to the overarching aims of the Comintern:

We remembered vividly that it was the huge demonstrations by Petrograd’s proletarian women that started the Russian Revolution on 8 March 1917. The will and self-confidence of the eighty-two representatives of the Communist women of twenty-eight nations came together in a unanimous resolve. Our 1922 International Women’s Day must be a manifestation of the masses for Communism, an irresistible outcry against the bourgeois social order and in favour of the proletariat’s usurpation of power. It must prove that we Communist women not only want to act, but can also do so. (36)

Röda Röster, no. 5 1922

Unlike communist women, social democratic women were using IWD, week or month, as a way for women to campaign with slogans directly associated with equality in order to get women to join their organizations. It was the policies for everyday women, such as equal pay and the protection of mothers and children, that were on the agenda of social democratic women’s organizations’ IWD celebrations.

World peace was the most important IWD message after World War II. When the Socialist International started to send official messages again in 1955, the messages were similar to those of the Comintern, which were connected in a larger context to peace as an important task for women.

[...] We socialists believe that a commonwealth of plenty, social justice and peace can be established.

We call upon the women in the free countries throughout the world to join us in the great struggle for this aim, the struggle for freedom, peace and welfare for all.

Morgan Phillips-Chairman

Julius Braunthal-Secretary

Margarete Kissel-Women’s Secretary (37)

Broadening the message by trying to integrate IWD into a larger political context was also emphasized by the fact that it was signed by the chairman, the secretary, and the women’s secretary. It was the period in between the wars in Korea and Vietnam and the age of a new type of war.

One of the more important actors during this period was the WIDF, which was founded in 1945. The Swedish branch, the SKV, was until the end of the 1960s probably the group most active in IWD in Sweden. The WIDF was also among the groups that organized a celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of IWD in Copenhagen in 1960 and continued to be active even after 1960. It was a meeting with a historical perspective reminiscent of the origins of IWD. Women from seventy-three countries met in Copenhagen in April 1960 and discussed the development of equal rights for men and women from a historical perspective. It was a truly global gathering:

We invite all organisations and all those who uphold the just cause of women to give support to the International Women’s assembly which will be held in Copenhagen, April 21st-24th, 1960. This day will be a great occasion on which to honour the pioneers of the women’s movement, to review the historic past, draw new impetus from its victories, to help further success for women and to contribute to the realisation of their deep desire to eliminate war forever.

Statement released by the International Assembly of Women

ARAB Brita Åkerman’s personal papers

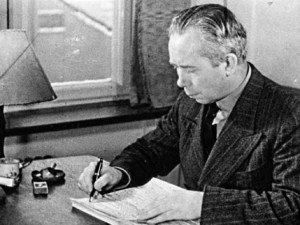

![WIDF congress in Vienna in 1958. Photo: (No information). Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.]()

WIDF congress in Vienna in 1958. Photo: (No information). Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.

Among the organizers were not only members of parliament, but also representatives of international women’s organizations, such as the WIDF, former delegates of the League of Nations and the ILO, Open Door International, the International Federation of Women of Legal Professions, and the president of the Committee of Soviet Women. (38) It was also a manifestation of women’s cooperation beyond national and political borders. However, behind the scenes, even this meeting struggled in the face of the political winds of the Cold War. The idea was to organize a meeting to which non-communist organizations of the free world would issue the invitations and where Soviet representatives would be welcomed. However, Eleanor Roosevelt was so upset about the organizing committee, blaming it for supporting Communism, that she both published a number of articles criticizing the organizing committee and refused to join it. (39)

The meeting was opened by Marguerite Thibert, former head of the ILO’s Women’s and Young Workers’ Division. The Swede Brita Åkerman gave a speech on the achievement of women. (40) It was this meeting that reintroduced the demands for gender equality as one of the main slogans; the historical perspective became an important political tool to mobilize women for IWD and it became a major international celebration outside the communist countries.

In 1969, the IWD celebrations on March 8 were organized by students at Berkeley University in the United States. This form of protest was even transferred back to Europe where the number of activist groups was increased and new demands were formulated, such as the right to free abortion; labour market issues, such as the six-hour working day and equal pay; and also day-care provision for all children. (41)

In 1975, during the first UN Women’s Conference, which was held in Mexico, it was suggested that IWD become a UN Day, and, in 1977, the general assembly approved the resolution. (42) Following the example from Copenhagen in 1960, this paved the way for cross-class strategies, not just in Sweden, but all over the world. Nevertheless, the UN worked hard to get rid of IWD’s socialist traits. However, this was not accepted by all of the women’s organizations as the quotation at the beginning of this text has illustrated: in 1981, in Sweden, Grupp 8 rejected working together with other women’s organizations. It wanted to maintain the socialist origins and, in the case of IWD, what Zetkin had called for: a ‘reine Scheidung’, a clean break. (43)

3. To reach out

![]()

International Women’s Day in Stockholm in 1995. Photo: Maria Larsdotter. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.

To get IWD’s message across required ways of organizing the gatherings in the form of demonstrations, meetings, and reports.

Today, IWD is definitely connected with 8 March, but this truly global synchronization is of a recent character.

The creation of synchronicity

Already in 1912 Swedish socialist women had received information from Clara Zetkin that the demonstration for women’s suffrage was to be held on 12 May. The Swedish journal Morgonbris published a translation of the leading article from Frauenstimmrecht, a German journal published by Zetkin for this occasion. (44) These translations, together with the date for IWD, give us some indication that not only homogenization, but also synchronicity was important in order to turn these manifestations into politically powerful ones. These synchronized manifestations then evolved into reports, printed in many of the socialist women’s journals, from local meetings, but also from meetings in other countries. Local, national, and international IWD messages were published in journals, international bulletins, and also in other countries.

During the very first years, IWD was always held on a Sunday, as it was the only day in the week when working women had time to take part in demonstrations. This says a lot about the difficulties of organizing working women due to their lack of free time. Even in 1913, the International Secretariat chose a particular date, 2 March, which was followed by many socialist women’s groups.

The synchronization of IWD on 8 March was the result of the Comintern’s women’s conference in Moscow mentioned above. How much this synchronization was followed in countries outside the Soviet Union is impossible to tell from the material stored at ARAB. This would certainly be worth investigating. Swedish communist women did not follow the Soviet idea of 8 March; instead, we can follow another strategy in order to compensate for the lack of synchronicity. The resolution of the Swedish communist women, published in their journal Röda Röster, is very instructive:

Resolution for international Communist women’s week

Women and men in . . . . . . . in number, gathered for a meeting during international women’s week on . . . March 1924, have decided to issue the following statement: [...].. (45)

Röda Röster, no. 3 1924

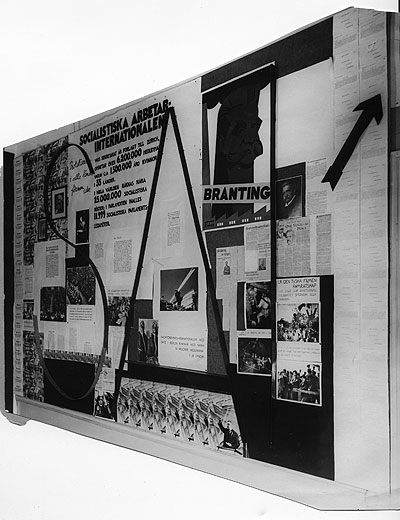

![Exhibition on the history of the Socialist International. Photo: Bertil Norberg. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.]()

Exhibition on the history of the Socialist International. Photo: Bertil Norberg. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

It was published with an empty space where the location, the date of the meeting, and the number of participants were to be filled in. This form was followed by the publication of the Swedish communist women’s official IWD message. The lack of synchronicity was compensated for by homogeneity of content, giving enough space to collect relevant statistics on the different meetings.

After World War I, it seems to have been more difficult for social democratic women to maintain the synchronization that took place during Zetkin’s time as head of the International Women’s Secretariat of the Second International. One of the reasons is that it took a much longer time for social democratic women to reorganize at the international level; another might be that the LSI Women’s Committee was less powerful than the Women’s Secretariat of the Second International. (46) But even the LSI Women’s Committee tried to synchronize IWD in 1929. The International Information sent a report from the women’s committee meeting:

Until now it has been impossible, due to organisational difficulties, to find one day for all the members of the Labour and Socialist International for the International Women’s Day.

International Information, 1929, 206.

However, in 1929, Austria, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and other countries agreed to follow the LSI Women’s Committee’s recommendation to organize a women’s month in April. (47) This was a very typical way to arrange women’s campaigning. During the inter-war years, not even in a country like Sweden was it possible to find one day for all the women to participate.

The collection of reports in the different journals helped to see the meetings that were normally spread out over weeks as a form of concerted action, transforming them into literally a mass meeting. Reading these reports is like being immersed in international information, and if the celebrations themselves did not create a feeling of internationalism, the accounts about the celebrations from different parts of the world did. The reports also show the links between national movements, which go beyond international coordination. Therefore, these reports are also of major use for an analysis of the international networks between both women and organizations. As the reports often include the name of the speaker, it is possible to analyze the density and strength of women’s international networks.

The reports roughly followed the same standards: the date, the place, and the number of participants were mentioned and sometimes even how many new members had joined the organization. A typical example is the report in Arbetarkvinnornas Tidning from 1941:

[...] On 9 March, a meeting was organized in Stockholm at HSB’s premises in Flemminggatan. The speaker was Valborg Svensson and there was an enjoyable programme of entertainment; eighteen new members.

In Malmberget, 8 March was celebrated with a grand meeting, attended by 350 people. The programme included a lecture by Filip Forsberg, music by a female trio, singing and mass recitation, and an enjoyable sketch that, among other things, served as propaganda for AKT (Arbetarkvinnornas Tidning); four new members. . . .

What is particularly pleasing about the meetings around 8 March is the tangible increase in political interest among the women. They are beginning to attend the meetings more than has previously been the case, and not only that-they want to take part in the struggle. They are signing up to be involved in the work on our journal and asking for information and advice about the work in order to get women involved. This bodes well for the future. (48)

Arbetarkvinnornas Tidning, no. 4 1941, 6.

This report also shows that IWD had a cultural dimension: music and dance as well as sketches were an important ingredient along with political speeches. The report also highlights how important the celebrations were for maintaining solidarity among members and that it was of major importance in order for any social movement to keep going.

Even international reports bear witness to how spread out the dates were. The International Information announced in March 1929:

The Socialist women of Austria will hold their “Women’s Day” from the 20th March to the 3rd April. During this time in all the Austrian provinces hundreds of meetings will be held, in the larger towns with demonstrations and processions.

[...]

The British Labour Party has already planned the activities of “Women’s Month”, which is to be the whole June. The Party has in previous years organised a “Women’s Week”, the success of which has led to the extensions of the work of this year.

[...]

In Germany “Women’s Day” is to be held from the 26th March to the 3rd April when great demonstrations will be held in many parts of the country. . . .

The “Women’s Day” in Switzerland is to be held from the 20th March to the 3rd April and in spite of the fact that the number of women organised within the Socialist Party is comparatively small, great efforts are being made to organise demonstrations and meetings in all local groups of the Party.

[...]

International Information, 1927, 106.

Despite the fact that many of these meetings were small, described in this way they conveyed the impression of a well-organized movement. As this information was sent in advance, it also had an important role in inspiring those groups which had not yet organized their annual campaigns.

![United Nation’s International Women’s Year in 1975. Photo: AND Zentralbild. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.]()

United Nation’s International Women’s Year in 1975. Photo: AND Zentralbild. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.

The lack of an ability to synchronically organize was compensated by a comprehensive presentation of both the planned activities and the reports about the activities that actually took place. This showed synchronicity through synchronized publications. This was not only an important means for a national movement, but it also channelled the feeling of internationalism between small local entities, bringing them together into a large international movement.

Since the 1970s, IWD has been celebrated on 8 March; it is not possible to answer how this synchronization emerged from the material stored at ARAB. The United Nations made it very clear in its resolution that it could be celebrated at any time of the year. Presumably, this was yet another attempt to get rid of IWD’s socialist traits. To analyze how this latest synchronization took place on a global scale would certainly be an interesting research subject and could probably contribute to our understanding of how global networks helped to transfer ideas and forms of action around the world.

The forms, ways, and dates of IWD differed in time and space. The development of how the celebrations were arranged is, though, very illuminative for our understanding of not only what ‘international’ meant over time and in different parts of the world, but also what the attempts to create a feeling of internationalism looked like. The synchronization by communist women was successful in the long run, which is borne out by the fact that IWD and 8 March are today inextricably linked to each other.

The magic of numbers

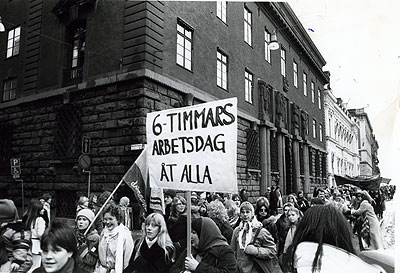

![International Women’s day demonstration in Stockholm in 1981. Photo: Ulla Bejum. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.]()

International Women’s day demonstration in Stockholm in 1981. Photo: Ulla Bejum. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.

The number of members is an important resource for every social movement, especially when it demands democratic rights. The more members it has, the more impressive the movement is, and it will attract the attention not only of the media, but also of political decision makers. As mentioned earlier, IWD was a way to increase the number of members of the labour movement. In the first half of the twentieth century, its political opportunities also depended on the number of countries that participated, as more countries meant more internationalism. When targeting a campaign at working-class women to join the movement, even the number of new members who had joined due to the celebrations was an important means of legitimating its political power and even the celebrations. The number of participants has to date been important in order to show the strength of the movement. Political strength could, therefore, be expressed by the marches of many people demonstrating for the same cause.

The very first IWD demonstration was held by Austrian socialist women, with 20,000 participants in a demonstration held on 19 March in Vienna in 1911. (49) This demonstration was also a political manifestation to highlight the masses of women who were excluded not only from suffrage, but also from participation in political organizations in general. In Austria, women were, together with immigrants and minors, legally excluded from membership of political organizations, which turned their demonstration into a powerful manifestation of women’s exclusion from politics. (50)

Many activists were afraid that IWD would not attract enough women to their own demonstrations in 1911 and that socialist women risked making fools of themselves and of the whole party, as Adelheid Popp, the grand lady of socialist women in Austria, reflected later in 1929 on the first IWD. (51) Therefore, the reports often included impressive participation figures, especially those in the international reports where the number of participants was rounded up to a figure that was even impressive for participants of smaller meetings.

Not only the number of meetings per organization was important, but also the number of participants. Swedish social democratic women reported in detail about the number of participants at each single meeting of the more than 100 IWD meetings that had been reported to the board of the National Federation of Social Democratic Women in Sweden (SSKF) in 1929. (52) The International Information did not publish such detailed figures for Sweden, but reported that meetings were held at 101 places, with 50-700 people participating per meeting. (53)

How important the number of participants was is also shown in the following quotation from a short memo about the police in Stockholm:

I base my opinion on the fact that the police stated the number of demonstrators to be 3,000, while experienced demonstrators estimated the number of participants to be between 5,000 and 7,000. (54)

Memo on the police in Stockholm

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén’s archive

After describing the average policeman as an inexperienced young man from the country, his ability to estimate the number of participants is questioned. The number estimated by ‘experienced’ protesters is almost double the number of participants. The estimated number of participants was often published in the daily newspapers and conveyed a picture of the political strength. For this reason, it was important for the organizers to question the police estimates.

The number of participants could also be increased by cooperating with other groups. In a proclamation published in Morgonbris no 14 in 1911, the executive committee of the women’s organizations wrote:

In 1910, at the International Socialist Women’s Conference in Copenhagen, it was decided to organize a “women’s day” in each country-a special day of agitation for women’s suffrage. In order to make such agitation as uniform and powerful as possible in our country, the executive committee of the Social Democratic women’s conference hereby proposes that this should become part of the working class’s big day of demonstrations and parades on 1 May. (55)

Cooperation with the labour movement was generally seen as an opportunity for demonstrating with many participants. Swedish working-class men had been given the right to vote in 1907 and male democrats had been criticized for promoting male adult suffrage in preference to adult suffrage. A joint manifestation might also have been a strategy to demonstrate an agreement on women’s suffrage, but probably also a demonstration for the Swedish labour movement that had lost many members during the general strike of 1909, which resulted in a divided trade union movement.

Although IWD was a socialist event, social democratic women cooperated with both men from the labour movement and other women’s organizations. In Sweden, in 1912, the Social Democratic major of Stockholm Carl Lindhagen gave on IWD a speech and, thereby, started a tradition of important men from the party taking part in the celebrations. (56) In 1929, International Information published a report from Greece where men were reported to have joined the meetings and demonstrations. (57)

In Sweden, even the women’s suffrage movement was involved in IWD by organizing a suffrage meeting together with social democratic women in 1914. (58) How popular this form of cooperation with other women’s organizations was during this early period needs to be investigated more and would certainly be an important contribution to dispelling the myth about the clear division among women’s organizations during this period.

The letter presented in the introduction, which was sent by Grupp 8 to the Fredrika Bremer Association, indicates the cooperation problems between some of the women’s groups referred to in the history of IWD and the split between socialist and other women’s groups. On 8 March 1979, the daily newspaper Arbetet reported:

[...] From the beginning, 8 March was thus a purely socialist day. It was the women of the labour movement who came together, with women’s rights and equality as their goal. The goal today is the same-although the women’s faction has split. Today, social democratic women, for instance, are, for example in Stockholm, demonstrating by themselves, while other women’s organizations, such as the Fredrika Bremer Association, Grupp 8, the Left Federation of Swedish Women, the International Immigrant Women’s Association, the Women’s House Group, etc., are forming a joint demonstration .[...] (59)

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén’s archive, Press cutting

When 8:e Mars kommittén had one of its meetings in 1980 to prepare the IWD demonstrations for 1981, the following groups had contributed money to the organization of the celebrations:

Grupp 8

The Women’s House Group

All Women’s House

The City of Stockholm Social Democratic Women’s District

The Liberal Party’s Women’s Association

The Stockholm County Social Democratic Women’s District

The Housewives’ Association, Home and Community

Women’s Struggle for Peace

The Syndicalist Women’s Association (SAC)

The Stockholm branch of the Fredrika Bremer Association

The Left Federation of Swedish Women (SKV)

Women of Labour

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

The Stockholm Women’s Centre Party

The cross-party breast cancer group

The Women’s Culture Association (60)

(8:e Mars kommittén’s archive)

This was a very impressive list of not only inter-party cooperation, showing the participation of all the political party’s women’s organizations, with the exception of the Moderate Party’s women’s organization, which celebrated IWD on its own. Even Grupp 8, which did not participate, had spent money on the demonstrations.

Cooperation with leading male members of the labour movement was an important way to gain legitimacy for the struggle of women for their rights in the labour movement. However, social democratic women used male party leaders to get their issues on the agenda, while the strategy used by Zetkin and other communist women since 1920 has also been to make women become more involved in general political issues and support the party.

Cooperation with women outside the labour movement is still one of the means of increasing the number of participants; however, it often makes a cross-class strategy necessary, a strategy that was not always regarded as legitimate when viewed from a historical perspective. This was a strategy that was not used and, instead, had been condemned by Zetkin since the conference in Copenhagen in 1910 as well as by Grupp 8 at the beginning of the 1980s. The cross-gender strategy employed by Swedish women during the very first IWD celebrations in May did not continue to be a fundamental element in Sweden, although it is mentioned in both the Swedish and international reports that leading Swedish social democratic men gave speeches at the official IWD celebrations.

Arranging meetings

Meetings had to be planned and arranged and this was time-consuming. The Swedish communist women discussed the problems of this during their board meeting of 29 March 1929 when they planned IWD in the form of a ‘Women’s Week’:

§ 5.[...] was of the opinion that the material had been sent way too late and felt it was an utter scandal that such a thing needed to happen since the women’s committee had, in any case, started planning the event in September of the previous year. Felt that mistakes had been made as the committee had spent time planning down to the last detail a women’s conference that has never yet been able to be held, while the more important work that required being carried out earlier had to be deferred. [...] Felt it was not surprising if the municipalities had not been able to organize meetings during the campaign as the material was not ready to be sent out until the campaign was already half over. (61)

ARAB Svenska kommunistiska partiet, Kvinnoutskott, minutes of 29 March 1929.

![International Women’s Day at Sergel’s Torg, Stockholm in 1981. Photo: Ulla Bejum. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.]()

International Women’s Day at Sergel’s Torg, Stockholm in 1981. Photo: Ulla Bejum. Source: ARAB, Ny Dag.

This illustrates very well that homogenization and synchronization could become a real problem if the organizers did not have the time to prepare the meetings in advance. One of the board members explained her own difficult situation as she was snowed under with work and that it was very difficult to say no to various requests from the party leadership.

Organizing meetings and demonstrations also meant in the case of IWD that, as long as it wanted to maintain its legitimacy, a lot of paperwork had to be done. Unlike the demonstration in Petrograd in 1917, the SKV was not just planning a march but was sending an application to the police in Stockholm for its demonstration to be approved. The application sent to the police in November 1980 contained the following:

The Stockholm District of the Left Federation of Swedish Women hereby requests permission to organize a demonstration on Sunday, 8 March 1981, in central Stockholm.

Planned procession route: Humlegården-Nybroplan-Hamngatan-Norrlandsgatan-Kungsgatan-Drottninggatan-Sergels torg.

Times: assemble at Humlegården 12.00, march begins 12.30, arrive at Sergels torg approx. 13.30.

Estimated number of participants in the demonstration: 5,000.

Aims of the demonstration: to celebrate International Women’s Day by showing solidarity with battling and oppressed women worldwide, and supporting the struggle for peace and for our right to work, the right to our own sexuality and other demands important to women in Sweden. The demonstration, which will include a number of women’s organizations and groups, will feature a great number of both large and small placards and banners. We anticipate there will be short speeches plus musical items and other entertainment in connection with both the start and finish of the demonstration. (62)

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén’s archive

The application to the police also tells us that Grupp 8 would be taking almost exactly the same route as the larger joint demonstration planned for 8 March, but about two hours later. In their application to the police, they wrote:

[...] On account of International Women’s Day, we wish, in keeping with tradition, to organize a public procession, assembling in Kungsträdgården at 14.00. (63)

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén’s archive

This meant that two demonstrations were held in 1981 within four hours of each other in Stockholm, almost as was the case on May Day. Interestingly, the reasons for their applications differed: Grupp 8 referred to the demonstration as being a tradition, while the SKV cited the reasons as being women’s subordination in society and the struggle for peace. Both documents can be found in the archives of 8:e Mars kommittén, which are a real gold mine if one wants to study how IWD was organized in the 1980s, and are probably very typical of the work done in different political women’s groups since the end of the 1960s. The files include everything from discussions on the content, the form, and the finances to an evaluation of the IWD held in Stockholm in 1981.

In a letter to the invited organizations, Britta Ring, vice president of the Stockholm branch of the SKV, wrote that she was hoping immigrant women could come up with a slogan that represented the main demands of immigrant women in Sweden. (64) This meeting was supposed to show plurality, and not homogeneity, in order to attract as many participants as possible, but maybe at the expense of an extreme categorization, a reinforcement of the categories, such as ‘immigrant’ or ‘lesbian women’, instead of supporting all of these interests under the umbrella of women’s demands.

In their evaluation of the event, the organizers were satisfied with the outcome; IWD had, according to them, never before had so much media publicity. A homogenization of slogans they had planned in advance had failed to materialize and, instead, their press release contained nineteen different slogans, one for each women’s group that had joined the joint action. The groups could not agree on the slogans that had been previously discussed, of which three were international and nine with entirely Swedish political demands. While most of them referred to women’s rights and peace and disarmament, the Fredrika Bremer Association was the only organization demanding parental leave for fathers as a children’s right to be with their fathers. (65) It also turned out that women were not allowed to bring their party banners, or any banners that did not directly symbolize women’s groups. (66) The papers of this group also show how much technicalities mattered:

[...] For this reason, human contact is required between the microphone work and the work at the start. One person should be detailed to walk at the head of the procession; the police cannot be relied upon in this respect. One person should gather everybody together and start the demonstration from the “launch pad” and one person should operate along the route and provide information on the start a few minutes ahead; “start” in the sense of the approach to the launch pad. On arrival at the assembly point, one person can stand by the loudspeakers and one person can guide the procession to the designated place, pick out massed flags, etc., and collect in megaphones. (67)

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén, Evaluation of 8 March 1981.

Getting one’s message across also depended on the technical equipment and the organization using it. This was probably an even more difficult task during IWD celebrations at the beginning of the twentieth century, but very little is known about this.

The international ‘character’

I have already mentioned how the feeling of internationalism was created by the homogenization and synchronization of IWD, but internationalism also had to be part of the very meeting women were taking part in and something that had to be manifested locally. An opportunity that only important and, with this, probably rich socialist women could use before World War II was to express internationalism through inviting foreign speakers. I have already mentioned the cases of both the demonstration in Berne in 1915 and the meeting in London in 1941 where several well-known socialist women gave speeches; in both cases, representing their countries as a manifestation of an international protest against the war and the content and the speakers themselves contributed to the feeling of internationalism.

Showing solidarity with women who come to Sweden as refugees due to war and dictatorships is still done today by inviting them as speakers to important meetings. Liselott Croner was one of the speakers in 1949 and she used her entire speech to talk about the persecution she had experienced in Germany, but also about all the help she had received in Scandinavia, thus illustrating the international solidarity she had experienced herself. (68) An IWD celebration held in Stockholm in 1979 showed a film about the children who had disappeared during Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, and different women’s groups and Chilean refugee choirs were part of the programme. The meeting was concluded by singing ‘The Internationale’. (69)

The organizers of the IWD celebrations in Stockholm in 1981 regarded immigrant women as a contribution to internationalism in a very specific way, almost as a form of decoration that would add the necessary finishing touch to the celebrations. In the evaluation of the 1981 IWD, the difficulty in finding international slogans is mentioned. The material conveys the impression that the invitation to the International Organization of Immigrant Women in Stockholm (IFFI) was an ad hoc solution. Although this group was invited, it was not at the centre of the organization:

The appearance by our immigrant women was much appreciated, from what I have heard. Our idea was to enliven the information with singing and music, but many had perceived the on-stage appearances as entertainment. Perhaps our approach should be that the stage is used for entertainment, interrupted now and then by information. The happy, fast, and entirely incomprehensible songs from Eritrea greatly delighted the children (from what I have heard), which shows that comprehensibility and texts are not a must when it comes to winning the audience’s approval. The immigrant women’s contributions were very successful here and had deserved better presentation and organization than we were able to hastily provide and by means of improvisation, [...]

The biggest plus points were that we were supported by so many women’s organizations-a sort of united front-and that its image was so international. (70)

ARAB 8:e Mars kommittén, Evaluation of 8 March 1981

Despite these descriptions, the representative of the immigrant women’s group said in the evaluation that she felt integrated and supported by the other women but would need more information earlier in order to take part in the preparations. (71)

One volume in the SKV’s archive bears witness to yet another way of women encountering and expressing international solidarity, despite the Iron Curtain, using very simple means. The volume is filled with postcards written during the 1950s and 1960s and sent from different parts of the world. Most of them are from the Eastern bloc, but there are also cards from neighbouring Scandinavian countries congratulating the SKV on the IWD celebration. (72) These postcards are a very good illustration of the huge international networks of the organizations maintained by IWD. How much these networks could be used for other political purposes is another question that cannot be investigated here. The postcards themselves, especially stored in one archive box, symbolize women’s international solidarity and are an impressive number. This form of international solidarity circumvented the barriers of the Cold War. The question is simply, at what rate? There is little knowledge and analysis of the consequences of the Cold War for women’s international cooperation and solidarity. Even here, IWD could be used as a prism for an analysis of this historical situation. An analysis not only of the people included in these networks, but also of the range of countries they were in touch with on different qualitative levels can show how international networks developed.

The way the international character of IWD has been conveyed over time has varied a lot. While synchronicity and homogeneity were created by a standardization that was a typical expression of globalization around 1900 in order to convey the feeling of belonging to one global movement, pluralism, despite synchronicity, has taken over since the 1970s. In addition, the size and density of international networks also seem to have changed, at least from a Swedish perspective. The impressive gathering in Copenhagen, with women representatives from as many as seventy-three countries, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary appears not to have been beaten. Rather, the high level of gender equality in Sweden seems to have rendered international solidarity a superfluous tool with which to fight for the improvement of Swedish women’s rights. This stands in contrast to the inception of IWD when international solidarity was also part of the struggle for the improvement of one’s own situation. Since the 1970s, IWD has become a manifestation of solidarity from women in the Global North with women in the Global South.

The different ways of getting IWD’s messages across have changed a lot over time, from an original manifestation against middle-class feminists, who demanded suffrage and, according to socialist women, were blind to the class consequences of their demands, to cooperation between women’s organizations with an initiative from non-communist women. It went from a campaign to win new female members for the labour movement, where women’s issues were not an important matter, to a truly global UN Day for women’s rights and peace.

4. Storytelling

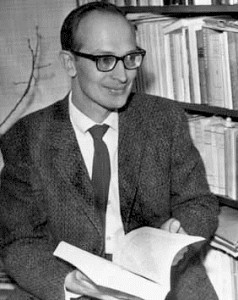

![Alexandra Kollontay (1872-1952). Photo: APN. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.]()

Alexandra Kollontay (1872-1952). Photo: APN. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

‘A narrative is the key to everything’ as some people say, this is also true for the story of IWD and the way activists told it, and still tell it. Although there is only little historical research on the development of IWD, the story about its origins makes a substantial contribution to its longevity by legitimizing its existence. This is done in two ways: first, it is recounted that it is a long-standing tradition to celebrate IWD. Second, the different stories told about the origins can be, and were, used to legitimize women’s positions in a specific political movement in a certain historical context.

The longer the celebration traditions are, the more powerful they are as political symbols today. However, the long-standing IWD celebrations are a story about variations of the aim, the content, and the form in which it has been celebrated: the different ways it has been celebrated by social democratic and communist women during the first half of the twentieth century are the first indication of this; the ways it has been celebrated since it became a UN Day are another.

It is probably since 1920, when Alexandra Kollontai gave a speech on IWD, that the history of the origins has become a recurring subject during the IWD celebrations. Not only journals, but also discussions on the organization of IWD are filled with these stories. Depending on who is telling the story, in which situation, and under what historical circumstances, the stories differ in the ways they are told. Temma Kaplan has written a short article on the socialist origins of IWD, in which she has discussed some of the different stories. While many believed that the day was originally celebrated to remember a brutally repressed strike by female textile workers in New York, Kaplan shows that the textile workers’ strike never took place, and nor, in 1907, was a day of celebration held to mark its fiftieth anniversary. This was only a story told by French communists in the 1950s. (73)

In 1973, the SKV’s journal Vi Mänskor published Kollontai’s IWD speech from 1920 in a translation from an English-language pamphlet to Swedish:

[...] 8 March is a historic and memorable day for workers and peasants, for all Russian workers and for all the world’s workers and peasants. This was the day when the great February Revolution broke out in 1917. It was the working-class women of Petrograd who started the revolution. They decided to raise the flag of rebellion against the Tsar and his henchmen. This is why International Women’s Day is for us a day of dual significance. (74)

Vi mänskor, no. 1 1973

Kollontai’s historical description is introduced by a short text written by the editors of Vi Mänskor, in which it says that Kollontai is recapitulating the history of IWD that is short, but rich in honours. (75) Kollontai’s narrative is probably the mother of many of the narratives told later in resolutions, articles, and brochures published by women’s organizations. In her historical account, Kollontai acknowledges American socialist women as the founders of IWD, when, on 28 February 1907, they held a major demonstration all over the country in order for working women to campaign for women’s suffrage. She then goes on to write about the second international socialist women’s conference in Copenhagen and acknowledges Zetkin without mentioning the other German women who had signed the motion. It is part of the construction of Zetkin as the sole heroine of the socialist women’s movement. However, Kollontai also refers to women’s hunger demonstrations all over the world during World War I that made women conscious of the need for political rights and turned suffrage into the key to political participation. Kollontai also gives a detailed account of the development of dates, pointing out that the historical meaning of 19 March, which was chosen for the first celebrations in 1911, was a reminder of the uprising of the working-class against the King of Prussia in 1848. By choosing this date and remembering it, socialist women opted to give IWD a revolutionary touch. And so do the following accounts of how the first celebrations were conducted. It is a story about masses of women, crowded premises, an unexpected success, and, in her speech, she tells the story of the confrontation with an aggressive police force. (76) For the period of World War I, it is a story about women bereft of their citizens’ rights and denied passports and, with this, they were unable to travel and meet, and it was only the neutral countries which were able to arrange demonstrations and meetings and it is in this context she says:

International Working Women’s Day in 1917 has become a historic memorial day. On this day, the Russian women lit the flames of revolution and set the world on fire. The February Revolution is considered to have started on this day. (77)

Vi mänskor, no. 1 1973

What are the decisions of a bureaucratic conference compared to a revolutionary story about the hunger and uprising of the oppressed? With the historical development in Petrograd in 1917, not only the stories, but also the aims of IWD changed; the attempt to connect it to the 1848 Revolution was obviously not successful, but the story about hungry mothers and children gave IWD a meaning that could be used even after the democratic decision in Copenhagen. It is this story that is repeated many times. Kollontai organized IWD for 23 February 1917 according to the Julian calendar (or 8 March according to the Gregorian calendar) and it was celebrated the American way. (78)

Women in Petrograd left the factory- and breadlines and metalworkers followed the women’s demonstration and protested against the high food prices, which had increased enormously. Staple food that in 1913 cost thirteen kopeks had increased to eighteen kopeks in 1916. The price of soap had gone up 245 per cent during the same period. The same happened in most of the European countries and made women go out on the streets and demonstrate, more or less successfully, their consumer power. In Russia, however, two days after the women’s demonstration had started, the Tsar gave the order to open fire on the women and this was the beginning of the February Revolution. (79)

Even the introduction of IWD as a memorial day in the Soviet Union in 1922 is told with Zetkin as the one who took the initiative, which might be true, but the stories are less concerned with the Comintern meeting and the initiative taken by Bulgarian representatives. (80)

Another story told is the above-mentioned women’s demonstration on 8 March 1936, which is linked to the start of the Spanish Civil War. The question is, who could make use of these heroic and revolutionary stories and what were they used for? Moreover, which story did reformist women tell during this period?